Fan merchandise is said to have been born in the 1940s when music fangirls, or “Bobby-soxers” (named for the socks that girls often wore at the time), would scribble their favourite musicians’ names on their clothes. Music merchandise has since evolved into a globally celebrated phenomenon, and recent years have seen the wave transform into a tsunami that touches every industry – from high fashion to politics.

The internet has put fan culture, much like everything else, on steroids. After all, we live in a world where K-pop fans were able to, in June 2020, use their collective power to sabotage US President Donald Trump’s rally in Oklahoma with the power of social media alone.

Still, while fan power may be bigger and better than ever, merchandise has retained the original meaning it had back when only the few lucky concertgoers could buy and wear band T-shirts – a sense of identity and belonging.

At a Busted concert in 2004, I can remember being greeted by a pop-up filled with posters, plastic toys and jersey tops, all covered in the British rock band’s faces. Deciding that I needed a tangible connection to them, I bought two tops, a badge and a poster.

A model wearing a The Who band T-shirt outside Valentino during Paris Fashion Week. Band tees used to be merchandise bought at concerts. Photo: Getty Images

The validation I felt following that concert echoes Gen Z’s obsession with merchandise today. In 2020, though, it’s no longer a promotional extra at concerts – it’s a central moneymaking focus.

“Previously, merch was only accessible from vendors post-gig or festivals, making it hugely exclusive and therefore covetable (and really only seen in relation to bands and artists),” Hannah Craggs, senior editor of youth at trend forecaster WGSN, tells the Post. “Social media is now playing the lead role of rewriting the script on who Gen Z feels worthy of [their] followership and investment in limited edition online drops.”

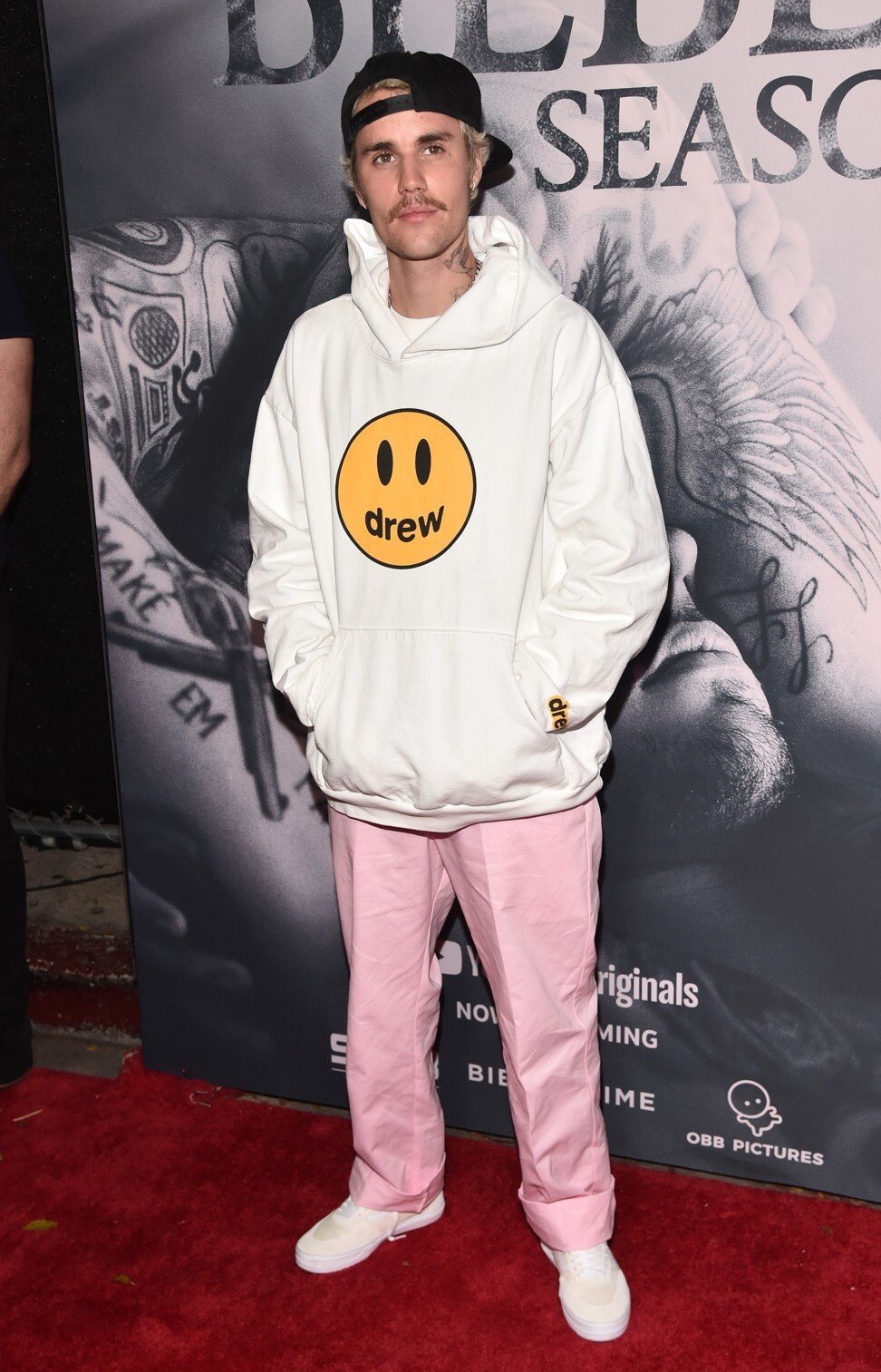

In July 2020, Billboard banned artists from using merchandise to boost their releases in the charts – a method rumoured to be used by Ariana Grande, Tekashi 6ix9ine, Justin Bieber and Travis Scott. Album bundles – clothing/product sold alongside single/album purchases – are common. In K-pop, album bundles (which include an impressive array of branded products, from food to glow sticks that flash in time to the music at gigs) sell out like they’re collectibles.

Then there are clothing lines like Justin Bieber’s Drew House and Cardi B’s store dedicated to her chart-topping single WAP. Merchandising possibilities today are infinite and fascinatingly excessive.

Emily Gordon-Smith, director of consumer product at trends intelligence agency Stylus, explains why the WAP store is so effective: “A full-range activation like the Cardi B WAP collection to coincide with the fever around the hit single is a smart one and really appeals to merch fans; particularly where we’re seeing unexpected or stand-out items, like the rubber macs in that range.”

Merchandise is becoming more creative and glamorous, and luxury designer collaborations are commonplace. We’ve seen – among others in recent years – Virgil Abloh, founder of streetwear label Off-White, design album merchandise for Travis Scott and Kid Cudi, Stella McCartney design for Taylor Swift and Gucci’s Alessandro Michele design for Harry Styles.

In September 2020, Balenciaga’s Demna Gvasalia announced a collaboration with Apple Music on a merchandise collection accompanied by a playlist curated by the fashion house’s community.

Craggs says that fashion is embracing merchandise to create a more relatable industry that appeals to Gen Z. “When designers work in tandem with their favourite artists, a fresh, unique and truly creative product is seen,” she adds.

Justin Bieber wears a hoodie from his brand Drew House. Photo: Getty Images

Luxury fashion’s love affair with streetwear has been blossoming for the past decade, and music merchandise in the form of clothing seamlessly slots into that marriage.

Having critiqued the surge of streetwear for blog Highsnobiety earlier this year, editor of StyleZeitgeist magazine Eugene Rabkin tells the Post why, psychologically, the 2020s might just be the decade of merchandise: “The fashion industry has just become another form of mass entertainment.

“The masses don’t care for design, because true design can feel unfamiliar and therefore intimidating. A logoed T-shirt is easy to understand. It’s fashion as kitsch.”

Gigi Hadid wearing former One Direction member Zayn Malik’s merchandise.

If streetwear has fuelled the hype, so has social media. “Everyone has an audience now, so we are pressured into broadcasting our tastes, whether it’s in brands, bands or politics,” Rabkin says. “Because of social media, our culture is a visual culture that turns everyone into a walking billboard.”

Merchandise appeals to older people, too. Take the ultra-stylish Biden-Harris clothing line as an example, designed by Tory Burch, Jason Wu, Proenza Schouler and others in support of the 2020 US election’s Biden Victory Fund for Joe Biden and Kamala Harris of the US Democratic Party, as well as the online Black Lives Matter clothing store – which donates all proceeds to the movement protesting against racially motivated violence against black people.

“Music and entertainment franchises are the obvious core backdrop, but there is more interest in political or activist merch now as well,” Gordon-Smith adds, “And that political [aspect] is more cross-territory and -age-demographic than we have seen before, which is interesting.”

The Biden-Harris clothing line was designed by Tory Burch, Jason Wu, Proenza Schouler and others for the 2020 US election’s Biden Victory Fund.

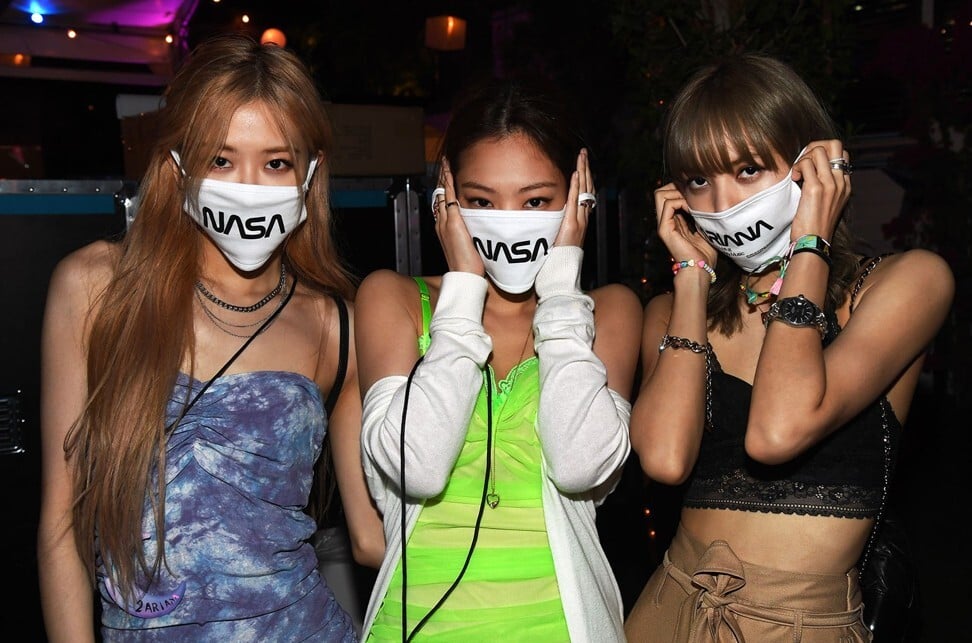

Blackpink’s Rose, Lisa and Jennie wear Ariana Grande’s Nasa merchandise collection. In July 2020, Billboard banned artists from using merchandise to boost their releases in the charts.

Our online and offline identities have converged thanks to our constant use of Instagram, TikTok and YouTube, which means clothing is a paramount signifier of who we are; and slogan tees make perfect personal branding.

Social media stars have tapped into fan merchandise, and are recognised by e-commerce marketplace FlashFomo founder David Nicholls, who creates collections for YouTubers like Bie The Ska (11.9 million subscribers), and JaMill (11.2 million).

The creative process at FlashFomo, where influencers sell products via flash sales, illustrates just how intimate fan merchandise has to be. “Our design team puts together a Pinterest board of the creator’s likes and dislikes, which goes into everything like the packaging, the product, the colours, all of that,” Nicholls explains.

Harry Styles teamed up with Gucci’s Alessandro Michele to create a T-shirt.

In September, Balenciaga’s Demna Gvasalia announced a collaboration with Apple Music on a merchandise collection.

“[Merchandise] always has something to do with a YouTuber’s saying or the niche community that they are a part of, it’ll be something particular to that. Sometimes they’ll create a brand name from scratch.”

From band tees to YouTuber hoodies, it’s evident that the feeling of belonging and identity that merchandise generates is what’s trending, not the clothes or products themselves.

Gordon-Smith says that this is what people want from fashion right now: “More personal purchases are increasingly going to be key, as we seek to buy less and to buy more meaningfully, so within this trend we can be sure to see merch continue to boom.”

Cardi B has an entire store dedicated to her chart-topping single WAP.

A fan, wearing a BTS hat, awaits a BTS concert. Photo: Getty Images

Merchandise, already flourishing before the coronavirus pandemic, has only increased in popularity since. As Craggs says: “Fandom and the draw of associated merch has certainly seen a shift, all accelerated by lockdown life and Covid-19 forcing audiences to search for new platforms of engagement.

“One important growth area to keep an eye on will be the emerging gamer market – set for serious expansion as new audiences engage in online entertainment outside now well-established on-demand services,” she continues. “Younger consumers are also tapping into above-the-keyboard dressing with boldly branded merch and clear slogans that are designed to be seen on-screen.”

Logomania, personalised fashion trends and epic online fan culture have triggered a mushrooming of merchandise. It’s a trend that serves a sense of belonging and establishes cross-cultural connections through shared obsession. During a time of widespread global loneliness, humanity needs that more than ever.

This article appeared in the South China Morning Post print edition as: Welcome to the era of fan merchandise