The Debate compiles some of the most impressive archaeological findings in the history of mankind

1 of 7

Cave paintings in the Altamira cave

The discovery of the cave was by chance. In 1868, a local man discovered the cavity while hunting and trying to free his dog that had become trapped in the cracks of some rocks. However, the discovery went unnoticed. Some time later, in 1875, Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola, a palaeontology enthusiast, visited the cave, but did not see anything remarkable. Two years later, accompanied by his daughter María, while her father was exploring the cave, he entered a side room and exclaimed: Look, dad, oxen! María had just discovered the first large-scale prehistoric painting known at the time. Bison, deer, horses, hands and other mysterious painted signs spread throughout the interior of the cave.

2 of 7

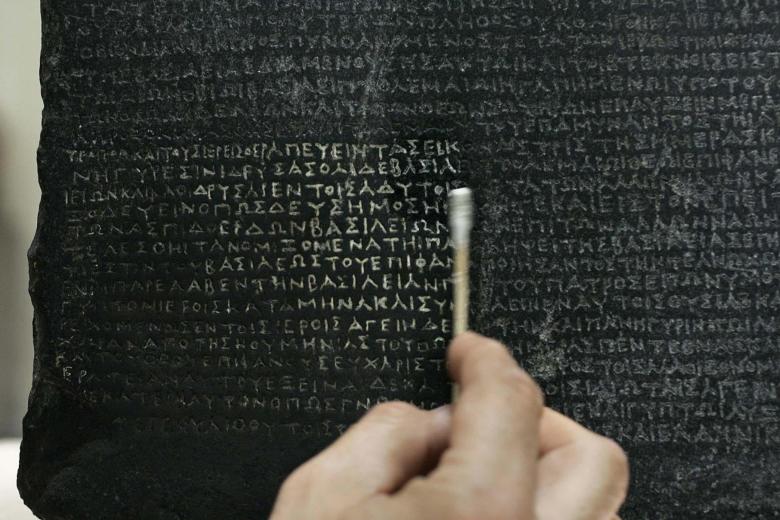

The Rosetta Stone

In 1799, while Napoleonic troops were rebuilding a fort near the Delta River in the town of el-Rhasid (Rosetta), they discovered the stone by chance. The same text was inscribed on the rock in three different languages: the upper part was in Egyptian hieroglyphics; the middle text was written in demotic script, and the lower part in ancient Greek. To decipher the different texts, the Frenchman Jean François Champollion intervened. With his extensive knowledge of ancient languages, especially Coptic – key to understanding hieroglyphics – he compared the different texts and realized that hieroglyphics had evolved into simpler symbols, giving rise to demotic writing, in addition to discovering that some symbols represented phonemes. In 1822 he published his first study on hieroglyphics. Champollion laid the foundations of knowledge about the Egyptian language and culture.

3 of 7

Antikythera mechanism

It has been described for many years as one of the most enigmatic objects in world archaeology. It was discovered in 1901 among the remains of a Roman-era ship on the island of Antikythera (Greece) at a depth of 45 meters. After carrying out several analyses and reconstructions, it has been determined that it is a mechanical calculator designed to predict the position of the Sun, the Moon and some planets, as well as to predict eclipses. It consists of a set of bronze cogwheel gears with astronomical signs and inscriptions in ancient Greek and is believed to date back to 87 BC.

In 2021, Michael Wright, a mechanical engineering specialist at the London Science Museum, found evidence indicating that the Antikythera mechanism could accurately reproduce the movements of the Sun and Moon using an epicyclic model devised by Hipparchus and also the movement of planets such as Mercury and Venus using an epicyclic model developed by Apollonius of Pergamon.

4 of 7

The Voynich Manuscript

This is one of the most mysterious books in the world. The author, language and alphabet used are unknown. Carbon-14 analysis dates the manuscript to between 1404 and 1434. It is thought that Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II acquired the manuscript for 600 ducats, but there is no record of this transaction. What is certain is that the book ended up in the hands of his advisor, the physician and pharmacist Jacobus de Tepenec, whose signature appears faintly on the first page. It passed through various hands until it ended up in the library of the Roman College, where several centuries later it was acquired by the antiquarian book dealer Wilfrid M. Voynich in 1912.

According to a recent study by the British academic Gerard Cheshire, it has been possible to affirm that it is a therapeutic reference book written by nuns in a lost language. The language that was baptized as Voynichese is a proto-Romance ancestral to the Romance languages of today such as Spanish, French or Italian that combines unknown symbols with more familiar ones.

5 of 7

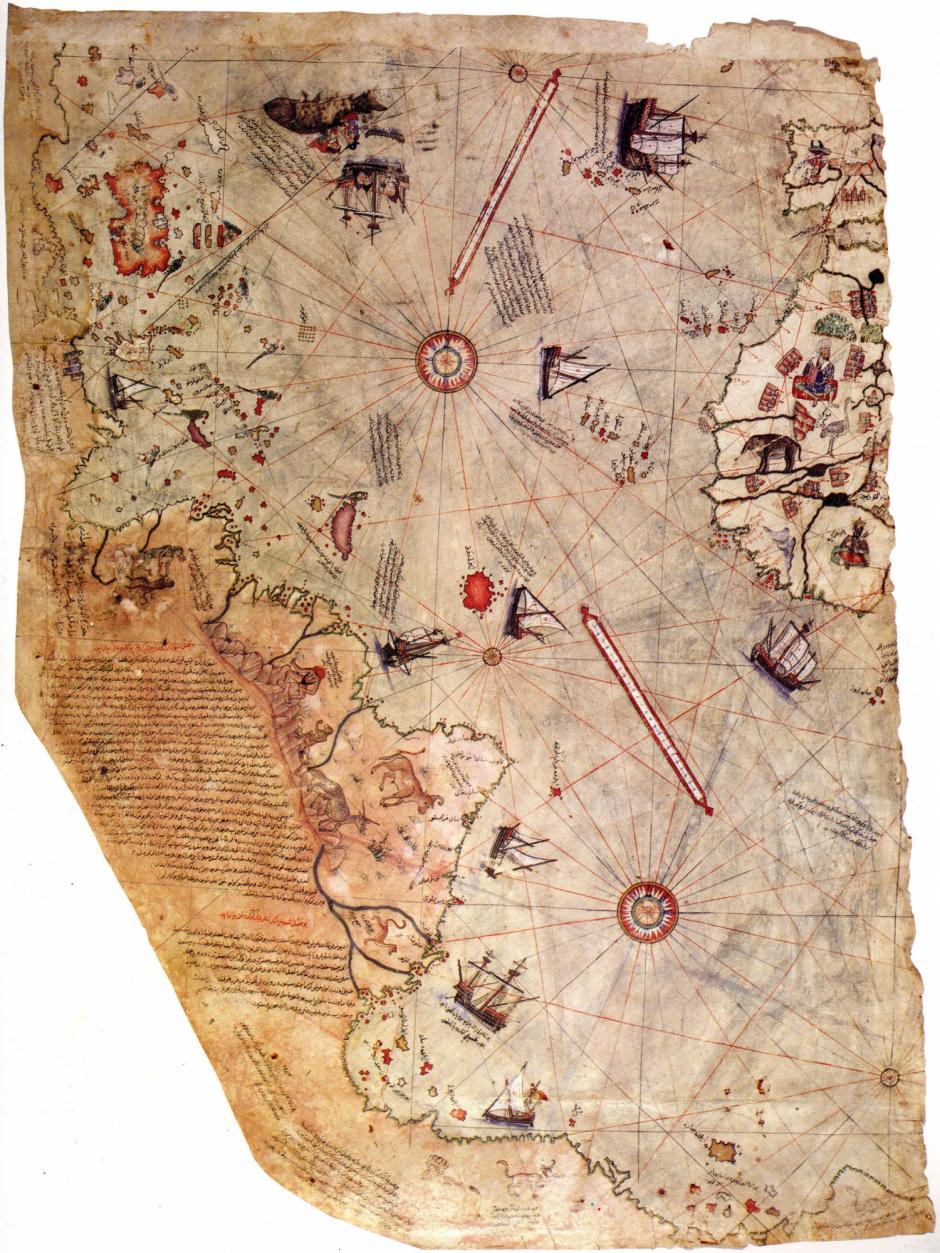

The Piri Reis map

This fragment of a map was created by the Ottoman admiral and cartographer Piri Reis in 1513 and shows the coasts of South America, Europe and Africa with astonishing accuracy. He used other pieces of different maps to make it, including a drawing by Columbus. It was discovered in 1929 in the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul (Turkey) when a group of scholars were working on classifying material in the archives section of the Ottoman Empire. They noticed the piece of a map that dated from the beginning of the 16th century and that bore some resemblance to the drawings on Christopher Columbus’s letters from his voyage to the New World. At first, it was thought that the map represented America and Antarctica, but this was not possible, since they were not yet known in Europe. It was later clarified that the map was loosely based on the ideas that were held at that time about what lay beyond the ocean.

6 of 7

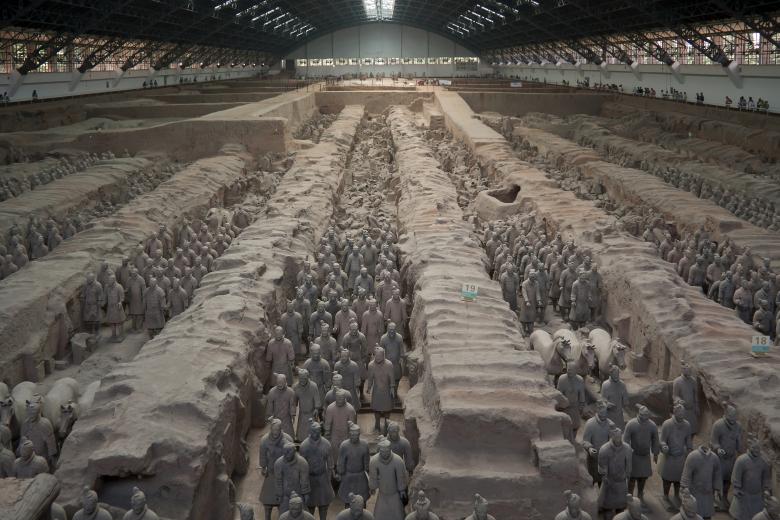

Terracotta Army

Next to the tomb of Quin Shin Huang, the first Emperor of unified China, there was buried a terracotta army distributed in three pits with more than 8,000 soldiers, a cavalry of 150 animals, 130 chariots pulled by another 520 horses and up to 40,000 arrowheads along with dozens of swords, spears, crossbows and other bronze weapons. The first of these was discovered in 1974 by chance by a farmer who was digging a well in search of water in an area where some remains had already been unearthed, but little importance was given to it until the news of the discovery reached the ears of the archaeologist Zhao Kangmin and he began the excavation. Later, in 1979, it would be opened to the public. A study was carried out which revealed that its construction began in 246 BC and ended in 206 BC. C. Furthermore, the purpose of these soldiers was to protect the Emperor’s tomb as part of the mausoleum model intended for the spiritual defence of the emperors. In 1987 the entire archaeological complex was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

7 of 7

The tomb of Tutankhamun

On November 4, 1922, a worker set foot on what would be the first step leading to the tomb of the Pharaoh Tutankhamun, untouched after three millennia. It was the British archaeologist Howard Carter, who on Lord Carnarvon’s orders supervised the excavations in the Valley of the Kings in order to find the tombs that had gone unnoticed on previous expeditions, who dug until he reached a mud door that led to the entrance to the tomb of the young pharaoh of the 18th dynasty. Inside, Carter found himself surrounded by a treasure of incalculable value in an excellent state of preservation, which led him to exclaim his famous phrase: “I see wonderful things!” – answering an impatient Carnarvon to know what was inside.

After weeks of meticulous excavation, in March 1923, Carter opened the inner chamber and discovered the pharaoh’s sarcophagus. Thanks to the work of the photographer from the Metropolitan Museum of New York, Harry Burton, we have photos that catalogue the entire find. In November 1930, the last objects were removed from the tomb.